Behind the numbers, a deeper play unfolds. The Guinean junta orchestrates a political masterstroke under the guise of democratic renewal — and the West applauds.

Record participation, orchestrated legitimacy

In Conakry, on the evening of September 22, 2025, Djénabou Touré, Director General of Elections in Guinea, announced a staggering 91.4% turnout in the Guinea constitution referendum, with 80% of ballots already counted. According to partial results, the “yes” vote leads overwhelmingly, surpassing 80% in most precincts — a result hailed as historic by local authorities.

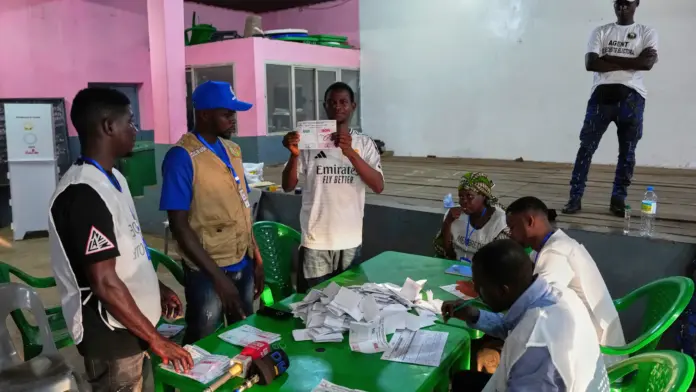

So far, 19,454 out of 23,662 polling stations have been “counted and validated”, Touré claimed. Over 4.8 million citizens reportedly cast their vote.

But such unanimous results in a politically tense country raise questions rather than celebrations. The near-total calm, the immense turnout, and the margin of victory — all point to a carefully managed process rather than a spontaneous democratic awakening.

A militarized transition dressed in civilian clothes

Officially, this Guinea constitution referendum aims to prepare the ground for upcoming presidential and legislative elections — scheduled, supposedly, for the end of the year. In reality, it serves a dual purpose: projecting stability abroad and consolidating military power at home.

Colonel Mamady Doumbouya, who seized power in 2021 by ousting elected president Alpha Condé, remains firmly in charge. He leads the so-called “transition” with the firm hand of a military officer, while projecting the image of a statesman abroad. This referendum, in essence, is not a step toward democracy — it is a referendum on Doumbouya himself.

That the “yes” campaign triumphed by such a margin is less surprising than revealing. The junta has used the referendum as a political weapon: to demonstrate popular support, marginalize the opposition, and gain international approval — all without truly relinquishing control.

A crushed opposition, a tamed electorate

Guinea’s political opposition, once vocal, has been systematically weakened. Calls to boycott the vote — led by figures such as Cellou Dalein Diallo — were largely ignored by the electorate. The reasons are telling: many Guineans, weary of endless chaos and elite dysfunction, now see the army as a vehicle for order, even at the cost of liberty.

Over 45,000 security personnel were deployed across the country to “secure the vote”. Unsurprisingly, incidents were minimal. The referendum was not a contest — it was a carefully staged ritual of consent.

There is no denying the presence of real public participation. But it was participation within limits — under pressure, under surveillance, and under control.

The West plays along, again

Predictably, Western diplomats and international institutions have chosen to interpret the referendum as “progress”, citing the high turnout as a sign of political maturity. But this is a familiar delusion, particularly in francophone Africa, where militaries have long mastered the art of mimicking civilian rule to keep real power intact.

Guinea now follows a pattern seen in Chad, Mali, and Burkina Faso: a military regime in civilian disguise, using elections and referendums to create just enough legitimacy to keep foreign donors engaged, while reshaping domestic politics to suit the men in uniform.

The Supreme Court will release final results in the coming days. But the outcome is already known. The referendum has succeeded — not in restoring democracy, but in solidifying the junta’s grip with a democratic mask.