Over 140,000 South Korean children were sent abroad between 1955 and 1999, often through fraudulent or coercive means. Now, for the first time, the state confesses, but too late, and perhaps for the wrong reasons.

A Tense Mea Culpa from Seoul

In a historic, and heavily belated, statement, South Korea has admitted responsibility for decades of abusive adoptions, acknowledging that thousands of children were removed from their families and shipped abroad under ethically and legally questionable circumstances. On October 2nd, 2025, President Lee Jae-myung issued a formal apology:

“The state did not fully assume its responsibilities. On behalf of the Republic of Korea, I offer sincere apologies and words of comfort to adoptees abroad, their families, and the biological families who suffered.”

A sympathetic tone, yes — but words come cheap after seventy years of bureaucratic denial, erased identities, and a generation of citizens sacrificed on the altar of national image and foreign diplomacy.

A State-Sanctioned Export of Children

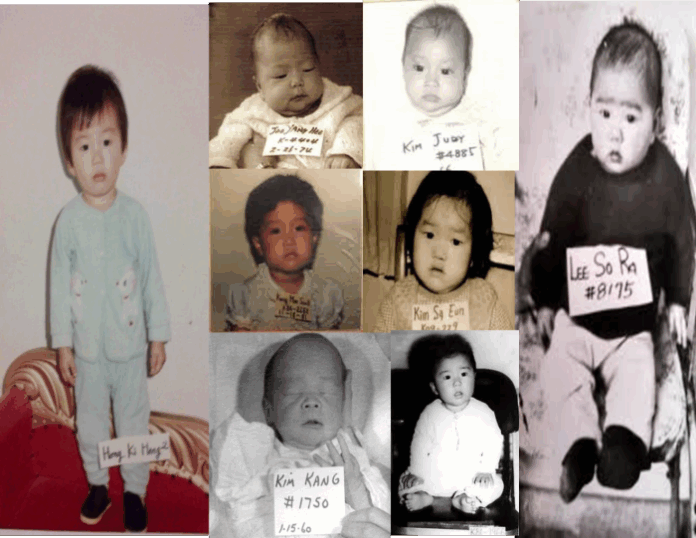

The term “abusive adoptions in South Korea” conceals a deeply organized and state-enabled system. From 1955 to 1999, over 140,000 Korean children were sent abroad — primarily to the United States, France, the Netherlands, and Scandinavia — in what became one of the largest child export operations in post-war history.

The recently published report from South Korea’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, following a two-year investigation, outlines how identities were falsified, parental consent was ignored, and adoption agencies worked hand-in-hand with state institutions to satisfy Western demand for “orphans.” In reality, many of these children had living parents — but that fact was often erased.

Post-War Ethnic Homogenization Meets Geopolitical Strategy

The roots of this operation go back to the aftermath of the Korean War (1950–1953), when children born to Korean mothers and American soldiers were seen as an ethnic blemish in a society obsessed with homogeneity. The West, especially the U.S., offered an “escape” through adoption, and Seoul — eager to solidify its role as a Cold War ally — seized the opportunity.

But what began as a form of social hygiene quickly turned into a geopolitical instrument. Adoption became a way for South Korea to curry favor with Western allies, projecting both humanitarian virtue and loyalty. For Washington and others, accepting Korean children was a form of soft-power projection, consistent with a broader Cold War playbook — one that saw Asia not as a continent of sovereign nations, but as a source of expendable human capital.

A Confession Without Consequences?

Let us be blunt: this public apology smells of political convenience. Facing rising internal discontent, a fragile economy, and growing criticism over his closeness to Washington, President Lee Jae-myung now seeks to clean the national conscience — cheaply, with words.

There is no mention of reparations, citizenship restoration, or even a framework to support the thousands of adoptees scattered across the globe. Many still suffer from lack of access to their original identities, records, and birth families. For all its poetic phrasing, this apology remains hollow if it is not followed by tangible action.

The Western Blind Spot

Perhaps most striking is the media silence in the West. When similar adoption scandals surfaced in Haiti or Cambodia, outrage was immediate. But here? Little to nothing. One must ask: is it because South Korea is seen as a “trusted partner”? Or because the adoptees now live in countries that refuse to question their own complicity?

The commission’s report confirms what many adoptees have long claimed — children were sent abroad to meet demand, not out of necessity. Far from humanitarianism, this was a form of social engineering, a demographic solution masked as benevolence. And it worked, largely because it aligned with Western paternalism and the belief that a child’s life in America or Europe was automatically superior.

Recognition Without Justice

Yes, Seoul’s admission is historic. But it is also painfully insufficient. Thousands of lives were uprooted, their identities stripped, their histories rewritten. And not only by South Korea — but with the passive or active participation of Western governments and agencies.

If this apology is to mean anything, it must be followed by:

- Reparations and support for adoptees,

- Transparent access to birth records and family histories,

- And a broader reckoning of the role played by international actors in this decades-long operation.

Anything less is just a public relations gesture — seventy years too late.