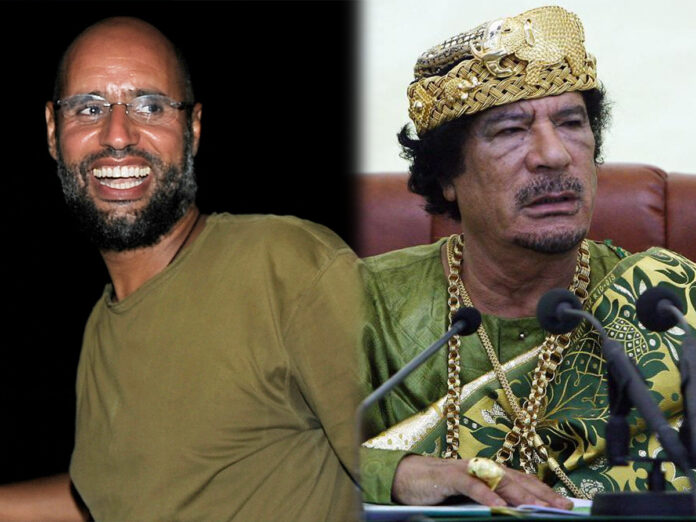

The son of the former strongman executed in Zintan. A clinical killing with symbolic weight.

Silent execution of a name still heavy with history

Seif al-Islam Gaddafi assassinated, the announcement, quietly aired by local Libyan channels and reluctantly confirmed by relatives, didn’t make global headlines. But it should have. The son of the late Jamahiriya leader was executed in his Zintan home, reportedly by a four-man commando who neutralized his surveillance system and shot him point-blank. No warning. No claim of responsibility. Just a political corpse and a chilling message: the Gaddafi name is not welcome in post-2011 Libya.

His advisor Abdullah Othman Abdurrahim confirmed the murder. So did his cousin, Hamid Gaddafi. Both offered few details — perhaps because none are truly needed. The operation speaks for itself. Precise. Silent. Unclaimed. But unmistakably deliberate.

Seif, the fallen heir of a failed order

Before the 2011 NATO-backed collapse, Seif al-Islam was the presumed heir to Muammar Gaddafi’s throne. Groomed in Western institutions, fluent in English, and seasoned in think-tank diplomacy, Seif had branded himself as the “reformer” within the dictatorship — the acceptable face of continuity. London saw in him the path to a “managed transition,” not a revolution.

But the illusion didn’t last. When protests erupted, Seif shed his reformist mask and promised blood in the streets. He became the regime’s voice of repression. Any Western goodwill evaporated, replaced by an indictment from the International Criminal Court for crimes against humanity.

Captured in 2011 by a militia in Zintan, he was sentenced to death in 2015 during a rushed trial in Tripoli — then mysteriously released under an opaque amnesty. Since then, he existed in a legal limbo: a fugitive, yet free; hunted, yet speaking.

A comeback bid that ended in bullets

In 2021, Seif shocked the international scene by submitting his candidacy for Libya’s presidential elections. It was a calculated gamble: betting on tribal loyalties and nostalgia for the pre-collapse “order.” Many Libyans, weary of foreign puppets and chaos, saw in him not a dictator’s son, but the last memory of national coherence.

His candidacy was both divisive and disruptive. For some, he represented dangerous regression. For others, he embodied strength, dignity, and resistance to external manipulation. The election never happened. Too many foreign interests, too many internal threats, and too many factions unwilling to see the Gaddafi name return.

The legacy may outlive the man

Libyan analyst Emadeddin Badi stated that “his death may turn Seif al-Islam into a martyr in the eyes of many.” That’s not mere hyperbole. In a land fractured by foreign intervention, tribal allegiances, and economic despair, the symbolism of his assassination could resonate far beyond the man himself.

His death eliminates a key obstacle to upcoming elections — but it also extinguishes a rare unifying figure for regime loyalists. Those who hoped to rally around him now find themselves leaderless. His absence may calm some factions. But others may radicalize.

Former regime spokesperson Moussa Ibrahim took to X (formerly Twitter) to mourn the killing as “a perfidious act”, claiming that Seif wanted “a united and sovereign Libya, safe for all its people.” These words, while theatrical, highlight a narrative of betrayal and martyrdom now available to Gaddafi loyalists.

A quiet killing, globally convenient

And then comes the real question: who benefits from this assassination?

Certainly not ordinary Libyans, caught in the vice of two rival governments: one in Tripoli, nominally legitimate and backed by the UN; the other in Benghazi, under the iron hand of Field Marshal Haftar and his sons. Neither side truly governs. Both serve competing foreign agendas: Turkish, Qatari, Emirati, Russian, and others.

A Gaddafi resurgence, especially through a son bearing the name, charisma, and nationalist rhetoric, threatened that delicate, manipulated balance. His death, staged with professionalism and zero noise, feels less like vengeance and more like calculated elimination. It was convenient. For everyone, except Libyans.

Libya buries a name, not a wound

Seif al-Islam Gaddafi assassinated, and with him, another illusion of order dies. His death won’t be mourned in Brussels or Washington. But in parts of Libya, his name represented a lost sovereignty, a memory of nationhood before it became a chessboard for foreign powers.

Removing him solves nothing. It only confirms what many suspected: Libya’s future will not be written by ballots, but by bullets, oil contracts, and secret deals made far from Tripoli or Benghazi.